INTERVIEW: Finding my voice through illustration – A journey

Leyan Wang - An illustrator tracing her journey from China to the UK. Through cross-cultural experiences and early criticism, she learns to navigate cultural responsibility and connect with global audiences through her art.

INTERVIEWSFEATURED

T Wu

5/27/20259 min read

Hello Leyan, could you introduce yourself first?

Hi, my name is Leyan. I’m an freelance illustrator currently based in London, and a graduate of the University of Edinburgh.

My work is mostly inspired by my daily life, personal interests, and cultural background. You’ll often find elements of folklore, music, film, and everyday moments woven into my illustrations.

How did you become an illustrator?

My journey toward a clearer artistic identity in illustration began during my MA studies. Back then, my undergraduate major was in Visual Communication Design, where most of my training focused on visual design — posters, brochures, visual assets for theatrical productions — essentially, supportive “backstage” work for stories rather than being the storyteller myself.

I started working as an freelance illustrator shortly after completing my MA, and it’s been a little over a year now. Currently, I mainly focus on illustration projects and developing my own creative IP.

What is your career journey?

When I came to Edinburgh to study illustration, our very first semester was centered around a single goal: “Find your own voice.” At the time, I was completely lost. For someone just starting out in illustration, having full creative control over your work for the first time is as exciting as it is overwhelming. At first, I thought it means to have a recognizable visual style. So, I dove into endless sketching and mimicry, trying out all kinds of techniques, collages, and styles inspired by the artists I admired. By the end of the semester, I started to notice something shift — my style was beginning to emerge.

But soon, I hit another wall. I had a style, but still no clear “voice.” It felt like a label — not something that truly reflected what I wanted to say. That clarity began to form in my second semester, when I started participating in local print fairs and student markets in Edinburgh. These events brought together students from different departments and even some of our tutors. It was my first time handling the full creative process myself — from making artwork to packaging it, to presenting and selling it. That experience became a turning point.

When I was in a position where I must explain and promote my own work, I suddenly realize how important it is to understand the core of what I am trying to express. This is how I began to understand my own voice — not as a fixed style, but as a way to connect, invite dialogue, and open a window into something meaningful.

Could you tell us about one of your work?

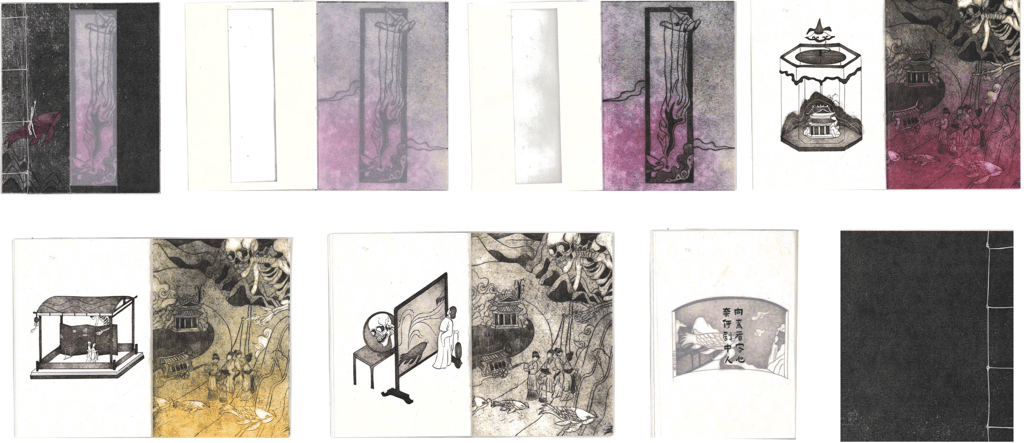

One of the pieces that received strong feedback was a dry point etching print I created in our school’s print workshop. It was inspired by puppet theatre from the Northern Song Dynasty in China, and I wanted to express the blurred line between illusion and reality. In the performance, puppet and puppeteer coexist in a space where everything seems small, yet equal — a metaphor for how we all exist, fragile but significant.

That piece generated a lot of curiosity from viewers. People asked me about “the story behind the giant puppet and the tiny humans. They wanted to know what puppet theatre meant, why I used certain textures, how I achieved the color.”

At that moment, I realized: when you present your work across cultures, there is often a gap — even a mismatch — between what you want to express and what others perceive. That gap is not a flaw — it’s an opportunity. It made me think less about whether I had told a “perfect story,” and more about how the story could spark curiosity and connection. What excites me now is not just conveying a narrative but creating that space where people from different cultures feel drawn to engage with the image and the idea behind it.

©️ Leyan Wang

After the puppet theatre piece, do you feel like you've found your own voice?

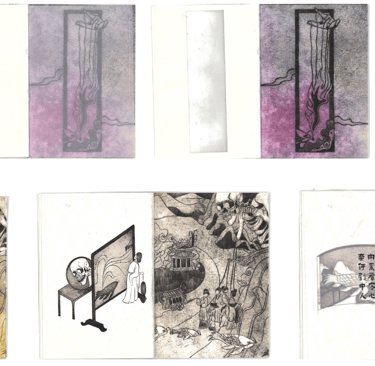

I think I’m getting closer. For my graduation, I did an independent project based on a story that’s very familiar to Chinese people — I adapted Painted Skin from Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio into a comic zine. At my graduation show, it attracted a lot of attention and many people read through the whole book.

After moving to London — and to be honest, compared to Edinburgh, London offers more platforms and opportunities for artistic output — I discovered a really well-known independent comic bookshop in Soho called Gosh! Comics. What makes it special is that they regularly feature independent publications from artists around the world.

At first, I didn’t think they’d accept my work, but I figured, why not just give it a try? I approached them with two of my zines, including Painted Skin. After talking to the team there, they showed a strong interest in the story and eventually decided to put it on their shelves. To my surprise, the book sold out very quickly. That experience made me realize — especially as a non-native English-speaking artist — that we often hesitate when promoting our work. We worry whether international audiences will understand or accept our stories, or whether they can truly grasp the cultural background behind them. But once you take that first step, you start receiving different kinds of feedback that naturally ease those concerns.

©️ Leyan Wang

Are there any critical comments of your work?

One of my early major projects was designing a Kunqu Opera-themed blind box series, back when the blind box trend was just emerging. At the time, it felt fresh and exciting—there weren’t many collectibles inspired by Chinese opera. The project was well-received on the surface: it was collected by the school gallery and even won awards. But when it was exhibited, professors from the traditional opera department viewed it—and I later learned they were quite critical. They felt I had oversimplified Kunqu, turning something deeply layered into something superficial.

At the time, I was frustrated I thought I was helping to modernize something younger people were drifting away from. But in hindsight, I recognize there was some arrogance in my approach. I hadn’t fully understood the responsibility that comes with adapting traditional culture.

That experience became a turning point for me. It taught me to slow down, listen more, and think more critically about how I engage with cultural heritage. Since then, I’ve been much more intentional about understanding the context, history, and meaning behind the traditions I reference in my work.

As an artist, how do you see those criticisms?

At first, I was quite resistant to criticism—I felt misunderstood. But over time, especially through my experience studying abroad, my perspective shifted into something more reflective and thoughtful.

When you're working within your native language and cultural context, it's easy to overlook certain blind spots. Back when I created that particular piece, I unconsciously marginalized older generations. I assumed my audience was young, and my goal was simply to get people to like the IP. In hindsight, that was a bit naive—even arrogant. I thought popularity equaled cultural promotion.

But after moving to Edinburgh, I had a moment of clarity during the winter torchlight procession. It was freezing, and I stood among a crowd that included people of all ages—locals and international students alike. The sense of shared tradition struck me. That event made me realize: real cultural transmission includes everyone. It's not just about renewal or rebranding; it’s about participation across generations.

When working on projects based on my own cultural heritage, I used to focus on technical accuracy—making sure I captured the right patterns, stories, and aesthetics. But many people from different cultural backgrounds aren’t as focused on those elements. What they're often more curious about is the process: how and why you make something.

That realization changed my creative approach. I began exploring non-linear narratives that could communicate beyond language and cultural barriers. It also made me more aware of whose voices are left out when we talk about "preserving" tradition. Ultimately, I’ve come to see criticism as a valuable tool—one that pushes me to grow, rethink, and engage more deeply with both my audience and my own intentions as an artist.

©️ Leyan Wang

In the UK industry, what difficulties you faced? What benefit you got?

While I’ve had the chance to present my work internationally, at this early stage in my career, I’ve found the challenges far outweigh the support I have received. As a recent graduate entering a mature illustration market, I often feel like I lack a complete creative system of my own. Unlike seasoned artists whose styles have been refined over years and are already recognized by the market, emerging illustrators like me are still in the process of trial and error—experimenting, seeking feedback, and slowly developing a voice. This becomes even more difficult when working across cultures and languages, especially when my work draws heavily on my own cultural background. If I don’t adapt my content to meet audience expectations, I often encounter more barriers and limitations.

That said, these challenges have also driven my growth. Initially, I relied heavily on text-based explanations to support my work, afraid my visual storytelling wouldn’t be understood, especially in unfamiliar settings like book fairs or exhibitions. But over the past year, I’ve learned to communicate more through visuals alone. I've experimented with non-linear narratives and embraced techniques like liubai (negative space) from traditional Chinese art, shifting the focus from explanation to experience. This process—of adjusting to a diverse, international audience—has helped me reflect more deeply on my own methods and has opened up new creative possibilities.

©️ Leyan Wang

What does it mean to you to be a successful artist?

At this stage, I think it’s still an ongoing question for me—something I’m constantly reflecting on. For now, my goal is to explore more possibilities within the field of illustration. Through my own work, such as adapting the story of Painted Skin into a comic format, I try to extend the narrative beyond the original text. One way I do this is by experimenting with non-linear storytelling. I chose this approach because I’ve been thinking deeply about how traditional art forms, such as classical theatre, have never remained exactly the same over centuries. Their vitality lies in their fluidity and transformation. In contrast, written language—while powerful—can sometimes feel more restricted due to structural or institutional limitations. Visual language, on the other hand, often offers more freedom to express these shifts and movements.

So, to me, becoming a successful artist means being able to use my work to open up new ways of seeing and understanding—especially for audiences outside of their usual cultural or generational circles. I hope my illustrations can serve as a bridge that connects people with unfamiliar ideas or perspectives, sparking curiosity and dialogue through visual storytelling.

What is your next step for your career?

My next step is to return to academia and pursue further study. This decision comes from the past year of exploration, during which I became increasingly aware of the vast, untapped potential of visual storytelling. I want to explore illustration not just as a craft, but as a system of knowledge—something that goes beyond its current, often narrow definitions as a tool for education or online content. There’s still a lack of academic language and frameworks to fully capture the possibilities of image-making. So I hope, through further research and creation, I can contribute to expanding those definitions and open up new perspectives on what illustration can be.

©️ Leyan Wang

What is your next project?

While the full details are still under wraps, I’m currently working on an independent publication focused on fragmented or damaged artifacts in museums. This project grew out of a shared observation among a few of us, all working across cultural contexts. We noticed that many broken or incomplete artifacts are often displayed in ways that flatten their stories—stripped of context, shaped by institutional narratives, and sometimes silenced by power dynamics. History, after all, is often written by the victors.

In this editorial-style publication, we’re trying to reimagine how these objects might "speak" if given the chance. I’m currently illustrating several of the artifacts, and this process has been eye-opening. As a museum visitor, I rarely had the patience to read every label, especially since many of them are written in rigid or overly academic language. But through drawing, I’ve had to research each object’s origin, condition, and journey. I found that the act of telling the story from different visual angles often brings surprising insights.

My hope is that this project can show how illustration has real potential in knowledge production—especially for those who might otherwise feel alienated from museums. If even one person finds a new sense of curiosity about cultural artifacts through our work, I’d consider that a success.

web: https://leyanwangart.com/

ins: @leyanillustration

小红书(Red Note):Leyan

Email: leyanillustration@gmail.com

Sound Behind Curtain

A place for all Asian artists.

© 2026 Sound Behind Curtain. All rights reserved.

Your gift keeps the curtain rising for Asian creatives.

About

Contact