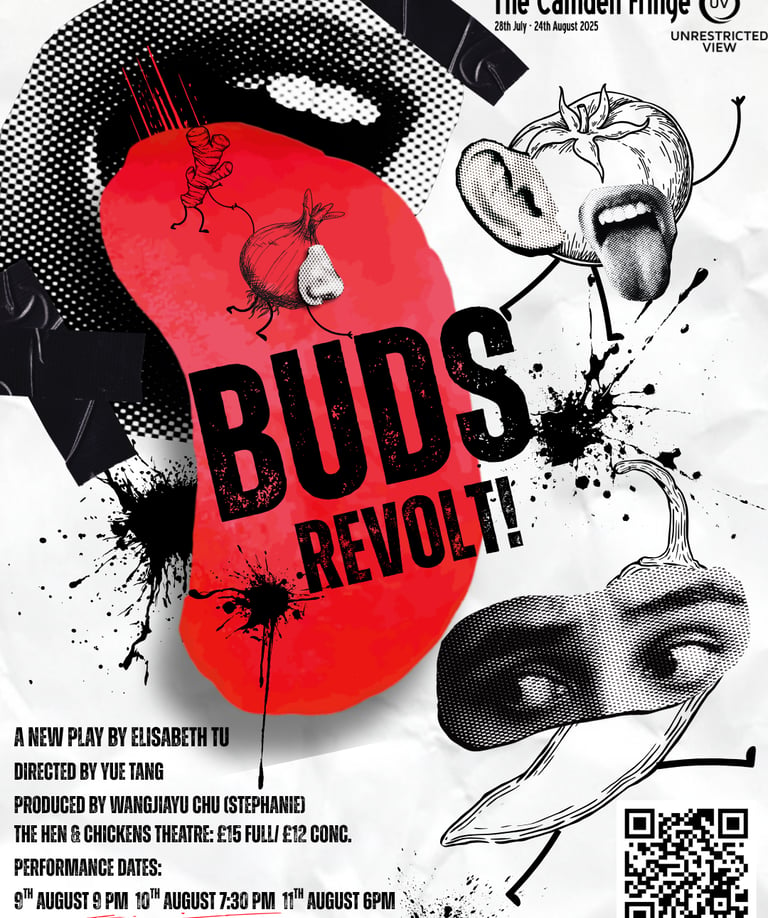

REVIEW: Buds, Revolt! - Where Does Belonging Lie for Those with Cross-cultural Roots?

Review Dates: 10th Aug 2025, @The Hen and Chicken Theatre, Camden Fringe

REVIEWSCAMDEN FRINGE 2025

Cassie Xue

8/12/20255 min read

Buds, Revolt! is an ambitious piece of absurdist theatre. This play boldly blends two-dimensional props with animated projection, and combines exaggerated performances with witty, satirical dialogue. The production draws inspiration from Samuel Beckett while echoing the judgmental upper-class British women of Oscar Wilde’s comedies. Despite the unfortunate theft of the projection equipment, which was used to store animation assets, right outside the theatre before the performance, this forced the team to rework the staging without their original technical setup. The absence of projections did not lessen the play’s impact; instead, it enhanced the audience’s mental engagement, creating an absurdist collision between thought and spectacle.

The piece begins with two upper-class British ladies (played by Elisabeth Tu and Hana Joi) engaged in a scene filled with judgmental gossip, reminiscent of Oscar Wilde’s sharp-tongued socialites. Their lines are laden with racial bias, such as that Asians should always have more plans, delivered without clear context and punctuated by odd counting parts. The playwright never clarifies what is being counted—perhaps immigrants outside the window or something entirely abstract—leaving it open to audience interpretation. The thick British accents and naturalistic tone of their chatter subtly ground the satire in reality, further reflecting the playwright’s evident admiration for Wilde. When repurposed to explore themes of nationality, race, and cultural identity, the effect becomes a sharp form of the theatre of the absurd.

Notably, the two women wear early 20th-century white undergarments and socks, without shoes but dressed with elegant hats, silk scarves, designer handbags, and a small dog. The stark contrast between their refined accessories and their underdressed bodies creates a visual satire. This incongruity deepens when two other characters, immigrants seeking identity, appear later in identical outfits—a symbolic doubling that links class critique with questions of belonging.

Mei (played by Elisabeth Tu) and Jessica (played by Hana Joi), two young women of immigrant descent, first enter with an introduction of self, including their assigned numbers, immediately evoking the counting motif introduced by the British ladies. Dressed in the exact white undergarments, they inhabit a stage-space constructed entirely from white cardboard cutouts—a kitchen where everything is colourless, sterile, and symbolically flavourless. Here, food is no longer food. As Mei prepares the Sichuan dish, mouthwatering chicken, she abruptly realises her taste buds have gone numb. How could she taste anything when the ingredients themselves are made of paper?

Their attempts to identify flavours through colour, their comedic and exaggerated physical performance, all highlight the artifice of what they consume, as the food isn't real. The recipe they found marks “home” on it, a word they pronounce with tentative curiosity. What is home, really? How to define it? Girls pronounce it oddly. They believe that “home” is the courgette. For Mei, without a clear sense of belonging or national identity, a non-native person cannot eat native courgettes. She cannot taste it—not because of a sensory defect, but because she, being “not native,” is told she must only consume what is “exotic.” A white sign reading EXOTIC is hung around her neck. Jessica physically pushes her across a chalk-drawn line on the stage, the other side representing exotic—a chilling and deliberate metaphor for racial segregation.

Two exaggerated “taste buds” presenters, once again portrayed by Elisabeth Tu and Hana Joi, burst onto the stage in cartoonish costumes, announcing the start of their show with a militant, pre-broadcast declaration. The repeated, fervent lines echo more like military drills than culinary enthusiasm. Mei and Jessica are mentally enlightened, now on the brink of chaos and revelation. As Chinese melodies drift in with every time Mie pick up the vegetables, their movements spiral into a physical frenzy, dancing between confusion and clarity.

Their declaration is straightforward: a mango is just a mango. It doesn’t become tastier because it’s native or exotic; no one buys a mango for its nationality. Similarly, Mei is simply Mei. The idea of being “native enough” is a construct—a symptom of grand narratives that aim to categorise and alienate. As she speaks, the words grow louder: native, not native, exotic. These aren’t labels she chose, but ones that have been stamped upon her. Eventually, Mei and Jessica finally get to taste real food. In contrast, the judgmental British ladies carry on with their ignorant, small-minded routines—unchanged, untouched, and unchallenged in their world of gossip and pretence.

Playwright and co-lead Elisabeth Tu has embedded the narrative deeply in her personal experience, growing up between Belgium and China before settling in the UK. Her transnational, multicultural identity influences the thematic focus of the piece. In Buds, Revolt!, food and taste serve as metaphors for belonging: when the tongue cannot detect flavour, what else has been dulled? What part of the self has been erased, overwritten, or colonised? The play’s exploration of race, nationality, and cultural identity poses a vital question: where does one truly belong? In today’s globalised yet still exclusionary world, identity is both multifaceted and regulated. What does it mean to be not native, or sufficiently native? The word "exotic" hung around Mei’s neck, becoming a powerful indictment of how racialised otherness is romanticised, commodified, and used to uphold boundaries.

The play’s stylised visual design—white paper vegetables, the sterile white kitchen, the unfamiliarity of the word “home”—resonates with the philosophical experiment of Pierre de Marivaux’s La Dispute, where characters are raised in isolation to uncover the “natural” human state. Elisabeth Tu imagines her characters in a similarly suspended space: the time is unclear, the place ungrounded. Mei and Jessica are like experimental subjects—innocent yet shaped by systems of control they cannot see. Meanwhile, the play’s deliberate absurdity and circular dialogue echo Eugène Ionesco’s The Bald Soprano, magnifying the illogic of societal definitions of belonging. Elisabeth Tu has mentioned Samuel Beckett’s Happy Days as a key inspiration, where laughter is laced with confusion, and theatrical absurdity gives form to the unspeakable.

Director Yue Tang delivers a skilful and cohesive staging of Buds, Revolt!, which enhances the ambition of the script without overpowering it. Whether through the performances of the two leads—Elisabeth Tu and Hana Joi balancing farce with precision—or through the carefully coordinated interplay of light and sound, the production demonstrates a high level of artistic integration.

From the orchestral overture before the house lights dim to the playful absurdist music that underscores comic beats, and finally to the shift into traditional Chinese instrumentation, the soundscape is intricately woven into the emotional arc of the piece. Music becomes not just an accompaniment but a narrative driver, intensifying both satire and poignancy.

Lighting also plays a vital role. The dark red hues during the taste buds television segment reflect the militaristic absurdity of it. The brighter, shifting lights during Mei and Jessica’s moments of revelation render their internal transformations visible. The interplay of shadow and light captures the very ambiguity the play aims to explore, how clarity and confusion, laughter and longing, coexist.

That said, one aspect of the play’s otherwise sharp dramaturgy does merit reflection: the most significant charged lines, those addressing race, identity, and national belonging, are often concentrated in speech-like sequences. While powerful in content, this density can risk appearing didactic. A more evenly distributed placement of these lines throughout dialogue and action might enhance their impact without disrupting the play’s absurdist rhythm. Yet, of course, this highlights the inherent paradox of absurdist theatre: it suggests meaning precisely by allowing the audience to experience it themselves.

To summarise, Buds, Revolt! is a bold, ambitious work—its theatrical inventiveness matched by the clarity of its critique. Through stylised satire and exaggerated visual language, it reclaims complex themes of national belonging, race, and identity with humour and bite. It stands as one of the most striking productions at this year’s Camden Fringe—a declaration of resistance, and a searching, spirited inquiry into where (and how) the cross-cultural roots can call “home.” It is also, unmistakably, a manifesto from the young generation of migrant, female, and non-binary artists refusing to be confined.

★★★★★

For more information, please visit: https://camdenfringe.com/events/buds-revolt/

Credits

Cast: Elisabeth Tu, Hana Joi

Playwrighter: Elisabeth Tu

Director: Yue Tang

Assistant Director: Evelyn Ker

Producer: Wangjiayu Chu (Stephanie)

Movement Director: Jonathan Layton

Set Designer: Joyce Hanjue Zheng

Costume Designer: Yuxin Lin

Video Designer: Sian Crowley

Lighting Designer: Yuhan Zhao

Accent Coach: Will Saunders

©️Buds, Revolt! Production

Sound Behind Curtain

A place for all Asian artists.

© 2026 Sound Behind Curtain. All rights reserved.

Your gift keeps the curtain rising for Asian creatives.

About

Contact